- Home

- Francine Pascal

My Mother Was Never A Kid (Victoria Martin Trilogy) Page 12

My Mother Was Never A Kid (Victoria Martin Trilogy) Read online

Page 12

“Where are we going?” I ask, because I can’t sit like a dummy, and besides I want to make sure he’s awake.

“None of your business.” What a charmer.

We drive around for fifteen minutes, and even though I don’t know where I am, still I get the impression that we’re going in one big circle. All the time we’re riding, Ted doesn’t say a word, but you can see he’s very busy planning something. Finally he seems to make up his mind and pulls over to the side of the street in front of an iron gate. I’m certain we passed this same place a few minutes ago. I give my mother a tiny poke in the side and whisper, “What’s up?” But she just shrugs. So we sit and wait. Obviously Ted has something on his mind but he doesn’t seem to have the nerve to do it. Finally he reaches into the back seat and comes up with a bottle of beer, gulps down half of it, and offers us the rest. We both say no thanks. He’s annoyed and polishes off the rest of the bottle and tosses it out the window. Pig.

“Your friend gets out here,” he announces. Obviously that’s what he was working up his nerve for. Well, he wasted his time. He must be nuts if he thinks I’m going to let him put me out in the middle of nowhere at midnight.

“Forget it,” my mother snaps back. “She stays with me.” Wonderful mother.

“I’m not turning over anything with a witness. You want to forget the whole deal?”

“I told you she knows all about it, so what difference does it make if she sees it?”

“It makes a difference to me. You don’t like it? Lump it.”

“Look, I gotta have that test.”

“Then tell your friend to get out.”

“Hey, wait a minute!” I thought I’d never open my mouth. “You can’t shove me out like that. I don’t even know where I am. How am I going to find my way home?” I probably sound like I’m whining, but I don’t care.

“Nobody said you had to find your way anywhere,” the freak says, capturing my whine perfectly. “Just get out of the car and wait here while we drive around the block and close the deal.”

“How long will it take?” I don’t know why I ask. Twenty seconds would be too long.

“I don’t know—give us ten, fifteen minutes.”

“But it’s not safe to stand here alone.” I turn to my mother for support.

“It’s all right,” says my wonderful mother, the rat traitor. “Nobody’s around.”

That’s just it. Nobody’s around. What’s the matter with her, anyway? People don’t just stand on empty streets late at night all alone. Especially a girl my age. What’s happening? At home she goes berserk when I want to take a bus after dark.

“Come on, you’re holding up the works,” says Mr. Vomit, who obviously can’t wait to get my mother alone in the car.

But I can’t bring myself to move.

“Don’t worry.” My mother tries to reassure me. “I’ll make it fast. You’ll see, we’ll be back in less than five minutes.”

I’m trapped. I can’t ruin everything for my mother just because I’m scared of the dark, so I have no choice. I open the door and sit there staring out.

“Move it!” This is so grossly unfair, but what can I do? I get out of the car, slam the door, and before I can even turn around I hear the car screech away.

Here I am, totally alone, not just on this street but in the whole world. I back up against an iron gate. It’s pretty dark, but if I stay perfectly still maybe they’ll think I’m just a big lump in the gate. They, of course, are the stealers, rapers, muggers, and murderers that my mother has been warning me about since before I can remember. Those same monsters she’s throwing me out to tonight.

It’s absolutely silent on the street and, with the trees tunneling the entire block, inky black. No cars pass. I wait, straining my eyes to catch a glimpse of Ted’s car coming around the comer. But there’s nothing but dark emptiness down there. Then something, maybe a cat or a squirrel, darts out in front of me and the lump on the gate leaps a mile. A dog howls somewhere in one of the houses down at the far end of the block and the numbness in my head begins to subside enough for me to make out some night sounds, crickets and things like that. There’s a slight breeze that rustles the leaves and carries the pleasant odor of fresh-cut grass. My mother’s probably right. I’ll be okay. Things were different in the forties, much quieter and safer, and you didn’t have to worry about being out alone at night.

In fact I’m probably safer alone in the street right now than she is in the car trying to fight off that moron. It feels like at least five minutes (more like five hours) have passed and they should be coining around the corner any second. By the time I count to forty-six (my new lucky number) the glare from their headlights should be visible. One, two, three … I’ll close my eyes and open them at forty-six … 45678910111213141516 …

Oh my God!

There’s a man. I can just make him out way down at the end of the street! And he’s coming right toward me. I can’t tell if he’s young or old but he looks big—I mean huge, tall, and fat. I can’t let myself jump to conclusions, but the odds are against me. I mean, sure he could be a plain old nice man, or he could be a mugger, stealer, rapist, or murderer. That’s what I mean, there’s only one little chance in four that he’s okay. It’s four to one against me. I’m in big trouble. He’s walking pretty fast. I’ve already jumped to conclusions, so now I’ve got to make up my mind…. If I run I’ve still got a good head start. But where am I going to run to? I don’t even know where I am, and then how will my mother find me? Maybe if I stand perfectly still he won’t see me. That’s dumb. He’d have to be blind not to spot me. I’ve got to stay cool. Oooh, I think he just spotted me. He hesitates for just a second, and now he’s walking slower than before.

Now that he’s closer I can see that he’s certainly not a priest. If that car doesn’t come by the time he gets up to the tree about fifteen feet away from me, I’m going to start screaming and running and pounding on doors and everything. I don’t care. He’s got another ten seconds.

Where is that car!

But it’s still black down at the corner, and now he’s right smack in front of me. He stops. My fingers squeeze around the rungs of the gate behind me. It’s too late to run. I’ll just hang on to the gate and scream and kick—

“Hello, young lady.”

“Hello,” I say before I can stop myself. Would you believe how well trained I am? I’m even polite to my own killer. He smiles and I can feel my face freeze in terror.

“Is there anything wrong?” he asks, trying to pass himself off as a terrific person just interested in my welfare.

“My, what’s a young lady like you doing out this late?” He’s still pretending he’s not a killer, but I’m not fooled. It’s just a matter of time before he attacks me. I’ve got to do something!

“Are you lost?”

“No, sir. Absolutely not. The soldiers are right around the corner.”

“Soldiers?”

“Out collecting silver. Hundreds of them. Pushing their doll carriages.”

Where is that car!

He looks at me hard for a moment. “Well,” he finally says, “I’m sure the soldiers are watching out for you. But look, I live just up that block, in that white house over there. Why don’t you come home and my wife will make some cocoa and we can call your parents and they can come and pick you up.”

Me? Go in that house with this old smoothie? No way. Then I see it out of the corner of my eye. The car. It swings into the block and here it comes.

“Speak of the devil,” I blurt to the man. “Here come my folks now.” The car pulls up and Ted and Cici peer out. “Hi, Mom,” I practically yell as I pile into the car. “Step on it, Dad, the general’s waiting.” As the car pulls away, I wave at the man and shout, “Remember the Maine!”

“What was all that about?” Naturally they’re both really confused. Then my mother says, “Am I supposed to be your mother?” I just shrug my shoulders and laugh. I mean, what do you do with that k

ind of question?

Then I tell them about my narrow escape. But all Cici does is say, “You’re loony. This is the safest neighborhood in the world.” She gives Ted a hate stare. “On the street, anyway. It can get a little dangerous inside a car.” I start to argue and rattle on about knifers and muggers and all, but Cici’s not really listening, and I can see she’s upset about something so I lean over and whisper to her, “What’s up?”

“Fink over here,” she says good and loud, “decided that two dollars isn’t enough, especially since he found out there are no fringe benefits.”

“Fringe benefits?”

“He expected me to put out,” she says, really zinging it to Ted, whose ears turn a brilliant scarlet. Suddenly he gets very busy staring straight ahead and concentrating so hard he could be driving on a tightrope. “And when I smacked him,” my mother continues, “he called the whole deal off.”

I glare daggers at him. Propositioning my own teenage mother! I could kill him right then and there.

“Ten bucks,” he suddenly says, “that’s the price. Take or leave it.” He pulls up in front of my mother’s house.

“Cici,” I poke my mother. “I want to talk to you for a sec.”

“Sure thing, Victoria, right after I tell this bum a few little things that are on my mind.”

“Forget it. The deal’s off, period.” Ted snarls. He’s hot to leave.

“You probably never even had the blasted test anyhow.”

“That’s what you think,” he says, and reaches into the glove compartment and pulls out what looks like a mimeographed page.

“Well, it doesn’t make any difference, I haven’t got ten dollars no how.”

“Cici.” I’m pulling at her sleeve, trying to get her out of the car so I can talk to her before she starts to unload on Ted, which she is going to any second.

“First thing you can do”—she’s so close she looks like she’s going to bite his nose off—“is drop dead! Then …”

“Cici …” Now I’m practically dragging her out of the car. “It’s important.”

“I’m coming.” But she’s not, so I whisper that I can lend her some of the money. That makes her practically jump out of the car.

“You can! Neato! How much?”

“I have six dollars”—it’s the emergency money my mother gave me, so in a crazy way it’s hers already—“and with your two that’s eight. Ask him, maybe he’ll settle for that.”

“Wait a minute. It’s really terrif, but I don’t know when I could pay you back. It would take me forever to save six dollars. I get thirty-five cents allowance, and even if I save the whole thing plus baby-sitting—I have this steady job two hours a week, that’s fifty cents, plus things like deposit bottles and—”

“Forget it. I don’t need it back for ages.”

“You’re really sensational, and don’t worry, ’cause I’ll pay you back even if it takes a year. Gee, thanks a million. Really, I …”

“You better ask the creep if he’ll take eight instead of ten. You never know with him, he’s so gross.”

“Okay, wait here.” And she goes over to the car and leans in the window. I can hear him giving her a really hard time. That’s a lot of money to turn down, considering he’s already done all the risky work—and stealing it, I mean. I’ve got a feeling something’s fishy. After a couple of minutes my mother comes back, really dragging.

“He says no dice. Ten or nothing.”

“What are you going to do?”

“There’s one last thing, but I hate to …”

“What is it?”

“A charity box. Oh, God, it’s just terrible even to think of such a thing.”

“You mean like a church?”

“Not exactly. It’s the USO. You know, they entertain the troops and things like that.”

“That doesn’t sound much like a charity. I mean, it’s not something serious like cancer or starving children.”

“But it’s the war effort, and I’ve collected from a lot of people and besides the soldiers really need it, and I don’t know …”

“How much have you got?”

“Oh, probably four or five dollars. I don’t know exactly—it’s in a sealed box.”

“You only need two dollars. You can pay that back in a month.” I know I was the one who was against the whole idea from the beginning, but now that I’m really into it I see we have to go all the way. After all, nobody wants to see their own mother go through the disgrace of being left back. Worse than that, not graduate. Especially when your mother’s such a terrific person. That’s heavy stuff—not graduating, I mean. When I weight that against some junky old song and dance routine, I mean, like there’s no choice. So here I am, trying to convince my mother that it’s ail right for her to steal from a charity box to buy answers from a moral degenerate to a stolen test. Super. Next thing you know we’ll be holding up gas stations. Of course, I do have an advantage. I happen to know that even without that two dollars, we won the war and there’s still a USO.

“All you do is send the money in anonymously. Nobody will ever know.” I guess I’m pressing, but I want her to pass that stupid old test. Turns out that she doesn’t need much convincing.

“Okay,” she tells Ted. “I’ll give you the ten dollars.” And it’s really weird, but I think he looks a little disappointed. I told you I think there’s something screwy. “Except,” she says, “I have to get the money from my room, so in the meantime you give the test to Victoria to hold and you can hold the eight dollars.”

Reluctantly Ted folds the test tightly in half, then in quarters, and hands it to me.

“Thanks, sport.” I can’t resist the dig.

“C’mon, Victoria,” my mother says, grabbing my arm. “Let’s go.”

“Hey, wait a minute!” The would-be defiler of my mother’s purity grabs my other arm. “Where’s she going with that test?”

“She’s got to come with me. I need her help getting up the tree.”

“What tree?”

“The one to the porch. That’s the only way I can get back into the house.”

“Yeah, well, I’m coming too.”

“Suit yourself. C’mon Victoria.” And the three of us sneak up the front steps and around to the back of the house. The thought of going back up that tree, especially barefooted, turns my stomach. I don’t know how I’m going to get back in, but I’m not going to worry about it now. Of course, my mother makes it look like a snap the way she shimmies up the tree and with one flying leap skims over the railing and lands silently on the porch. Even jerko is impressed. She ducks down and crawls along the porch and into the open window.

Fourteen

Watching her now reminds me how once about two years ago, we were on a picnic with two other families in some park on Staten Island, and I don’t know why, but everybody (the adults anyway) was kidding around and daring each other to do all sorts of crazy things like swinging from monkey bars and climbing trees. I remember that my mother climbed higher than anybody else, so high that I began to get a little worried. Everyone else thought it was hysterical, but it seemed kind of peculiar, even a little embarrassing to me. Now that I consider it, I guess it was kind of unfair of me to be embarrassed. After all, just because you’ve got children doesn’t mean you’re nothing but a mother. I’m hopeless when it comes to my mother. Everything about her is either embarrassing, irritating, or just plain confusing. I don’t know why I can’t just say she’s a great climber and let it go at that.

Anyway, here’s Ted and me waiting around for her, kind of kicking the dirt and not talking. By now he knows I can’t stand his guts and I’m sure he feels the same way about me. He probably thinks I screwed up his big chance with my mother. Little does he know he never had one.

It’s very quiet except for a funny scraping sound every few seconds. It seems to be coming from the house. There it goes again. I’ve heard that sound before but I can’t think where. It’s kind of like when you

shake … of course! She’s shaking the charity box, trying to get the coins out. I should have told her to stick a knife in the slot and let the coins slide out on it. It always works on Nina’s piggy bank. The sound stops and I catch a glimpse of my mother’s head coming out of the window. She’s across the porch and at the railing before I can tell her to get a knife. She clears the railing and fairly glides down the tree and lands with a clink of the coin box.

“I’ve been shaking this thing like mad and all I got out is fourteen cents. At this rate it’ll take me all week.” She’s still shaking the box furiously.

“Take it easy,” I say. “I can do it. All I need’s a knife.”

“They’d hear me for sure if I tried to get into the kitchen,” my mother says.

“How about if we break it?”

“No good. It’s metal.”

All this time the creep has been real quiet. Finally he says, “Well, looks like we’ll have to forget the whole thing.” And he starts to walk away.

“Hey, wait a minute,” my mother says, grabbing him by the sleeve. I still can’t get over how anxious he is to drop a ten-dollar deal. That really throws me.

“What do you want?!” He sounds really mean now.

“Your pocketknife.”

“Who says I have one?”

For a second my mother doesn’t answer. She just narrows her eyes and stares at him real hard. Just exactly like she does when she catches me trying to hide something. “I do.” And she’s practically tapping her foot. He hasn’t got a chance and he knows it!

“Let’s have it,” my mother commands, and Ted reaches into his side pocket and takes out one of those gigantic Boy Scout knives.

“Gimme the biggest blade you’ve got.” I try to sound like my mother. He opens the knife instantly and hands it to me. Obviously he’s one of those jerks who responds automatically when you give him an order. I wish we had known that before. Could have saved ourselves a lot of trouble. Anyway I get to work pushing the knife’s blade into the opening at the top of the box, and after a couple of experienced shakes the coins start to slide down the knife and into my lap. It couldn’t be easier and in less than three minutes I’ve got exactly two dollars in front of me. My mother is really pleased.

Runaway

Runaway The Sweet Life #2: Lies and Omissions

The Sweet Life #2: Lies and Omissions Little Crew of Butchers

Little Crew of Butchers Before Gaia

Before Gaia Save Johanna!

Save Johanna! Kill Game

Kill Game Sex

Sex Bittersweet

Bittersweet Wired

Wired Twins

Twins When Love Dies

When Love Dies Too Good to Be True

Too Good to Be True Chase

Chase Cutting the Ties

Cutting the Ties Amy's True Love (Sweet Valley High Book 75)

Amy's True Love (Sweet Valley High Book 75) The Perfect Girl (Sweet Valley High Book 74)

The Perfect Girl (Sweet Valley High Book 74) Kiss

Kiss Sweet Valley Confidential: Ten Years Later

Sweet Valley Confidential: Ten Years Later Dear Sister

Dear Sister Second Chance (Sweet Valley High Book 53)

Second Chance (Sweet Valley High Book 53) Killer

Killer Secrets and Seductions

Secrets and Seductions Dangerous Love

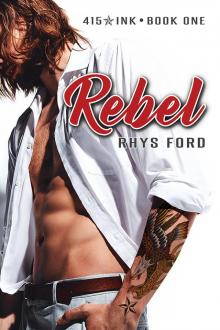

Dangerous Love Rebel

Rebel Shock

Shock Fearless: No. 2 - Sam (Fearless)

Fearless: No. 2 - Sam (Fearless) Racing Hearts

Racing Hearts White Lies (Sweet Valley High Book 52)

White Lies (Sweet Valley High Book 52) Fake

Fake Liar

Liar Flee

Flee Two-Boy Weekend (Sweet Valley High Book 54)

Two-Boy Weekend (Sweet Valley High Book 54) Love & Betrayal & Hold the Mayo

Love & Betrayal & Hold the Mayo Blood

Blood Double Love

Double Love Normal

Normal Betrayed

Betrayed My First Love and Other Disasters

My First Love and Other Disasters Wrong Kind of Girl

Wrong Kind of Girl Naked

Naked The Sweet Life

The Sweet Life The New Elizabeth (Sweet Valley High Book 63)

The New Elizabeth (Sweet Valley High Book 63) Blind

Blind Lost At Sea (Sweet Valley High Book 56)

Lost At Sea (Sweet Valley High Book 56) My Mother Was Never A Kid (Victoria Martin Trilogy)

My Mother Was Never A Kid (Victoria Martin Trilogy) Agent Out

Agent Out Tears

Tears Perfect Shot (Sweet Valley High Book 55)

Perfect Shot (Sweet Valley High Book 55) Regina's Legacy (Sweet Valley High Book 73)

Regina's Legacy (Sweet Valley High Book 73) Escape

Escape Freak

Freak Sam

Sam