- Home

- Francine Pascal

Love & Betrayal & Hold the Mayo Page 3

Love & Betrayal & Hold the Mayo Read online

Page 3

“It’s not that building.” She sounds positively glum.

“Big, small, it’s all the same to me.”

She mumbles something I don’t catch and heads around the back of what everyone is referring to as the social hall. That’s where they hold all the dances and entertainment. Terrific, we’ll be close by the fun place.

I accidentally drop my backpack and bend down to pick it up; when I get up again, I see Steffi picking up speed, and without a backward glance, she disappears around the back of the big hall. She’s acting strange. I hope it isn’t anything I’ve done.

I turn the corner of the building, but I don’t see her. She’s vanished—I must have come around the wrong side of the building, because there’s nothing here but a couple of rundown old ramshackle buildings in the middle of what looks like a rubbish dump.

The buildings themselves must be old storage shacks that they don’t use anymore. Half the shutters are falling off on the one closest to us, the front steps are broken and what remains of a front porch just barely clings to the building. Could our bunk be in the wooded area behind these shacks? It must be. I hope it’s far enough away from the mess. I pick up my backpack and start walking around the back of the shack.

“Victoria … Torrie … here.” A tiny voice come from inside the first shack. Then a head sticks out Steffi’s head, then I see the rest of her.

“What are you doing in there?” I ask.

She comes out of the shack gingerly moving her feet around, searching for a fairly safe spot on the porch, smiling the weirdest smile I’ve ever seen. Sort of what “I’m sorry” would look like if it was written in lips.

I open my mouth to say “What’s up?” Then it hit me. Suddenly I know exactly what’s up, and it’s not good.

“Oh, no, Steffi, I can’t believe it …”

“I’m sorry, Torrie, I swear it didn’t look this bad last year. I remember it as sort of quaint and charming.”

“Yeah, like the Black Hole of Calcutta.”

“Do you hate me or what?”

“I’ll tell you when I see the inside.”

I make my first mistake. I bound up the stair and right through the porch. And I mean through it. My foot sinks down up to my ankle and sticks there.

Steffi helps me pull it out. I don’t say anything. With one slightly scratched leg, I make my way to the doorway. And just stare. There’s only one thing I can think of to say. And I turn to Steffi to say it, but I don’t. Her eyes are afloat with tears. Nothing running down her cheeks, but one word from me would start a cascade.

“I just wanted you to come so badly. And you never asked me what it looked like. If you did I would have told you, I really would have.”

“Let me look again,” I say, and go back to the doorway. That was my second mistake. Looking again. It’s even worse the second time, I’m mesmerized by its awfulness. Eight terrible iron cots, most of them bent out of shape, with legs that don’t exactly touch the floor on all four corners and sagging hundred-year-old mattresses that look like someone bought them at the prison rummage sale. Each bed has a small cubby next to it. And I mean small. Three shelves on top and a tiny cabinet underneath. Perfect to hold everything for a short weekend, A single naked bulb (probably no more than forty watts) hangs down in the middle of the room with a broken piece of chain dangling from it, No problem reaching it if you’re over six three.

You can’t lie to your best friend. “It’s the worst, ugliest rathole I’ve ever seen,” I tell her.

“Sure, it needs some work, but if we all pitched in we could do it in no time.”

“Certainly—by Christmas.”

“Come on, Victoria. All it takes are some pretty curtains, maybe a cute bedspread, and some throw pillows. We could even get some pictures and posters. Maybe my mother could send me my Stones poster. We could hang it right over this rough spot,” she says, indicating a gaping hole in the wall the size of a bowling ball.

But Steffi is only warming up. She’s got a million ideas on how to turn this dump into Buckingham Palace, but I’ve stopped listening. Instead I’m hunting for the showers. But I can’t find them mainly because they aren’t there. The only thing in the back is one crummy toilet with a cracked seat, guaranteed to pinch you every time you use it.

“It’s positively primitive,” I tell her.

“It’s the country.”

“What country? Where’s the showers?”

“Just outside.”

“How just?”

“A little way …”

“Stef … fi!”

“Three blocks away. But they’re very tiny blocks Victoria. I know it’s not perfect, but …” There’s no way to finish that sentence.

I look around once more. It’s dark and ugly. And then I look at my best friend Steffi, and I feel dark and ugly because I’m giving her such a bad time okay, so it’s not great, but we could fix it up, and besides, what with all the parties and great things to do, we’re hardly ever going to be in the bunks anyway.

“My mother had some material left over from my curtains she could send to me,” I say.

Suddenly Steffi’s whole face lights up, and she runs over to me and hugs me. I hug her back, and everything is terrific again.

Then we both start to giggle, “It’s the pits, isn’t it?” she says, beginning to crack up.

“You think it’s that good?”

“Nothing a demolition crew wouldn’t cure.”

“Or a bomb.”

“I think they’ve tried that.”

“Well,” I say, looking around, “which bed do you think is the best?”

“The least horrendous or what?”

“Yeah.”

“Well.” Steffi starts walking around the room, inspecting all the bunks. “This is a tough one, but I think it would be terrible to be under the hole.”

“You mean the rough spot?”

“Yeah, the rough spot. Anyway, wise guy, I think that side near the bathroom is the worst. This side has the most light.”

“Mainly because the shutter is broken and hanging off.”

“When it falls off, you’ll really have some nice sunlight. Anyway, it seems to me that far and away the best bed in the bunk is …”

And just as Steffi is announcing her choice and pointing to the bed in the far corner nearest the door, a very pretty blond girl sweeps in and, with one quick survey of the room, flings her stuff down on the very bed Steffi was pointing to.

“That one!” Steffi finishes too late.

“Are you referring to my bed?” the yellow-haired girl asks, in an accent that’s a cross between phony American and phony British and sincerely unpleasant.

“It’s okay.” Steffi smiles. “Hi, welcome to the Black Hole of Calcutta. I’m Steffi Klinger, and this is my friend Victoria Martin.”

“I’m Dena Joyce Fuller,” she announces, with such aplomb that I feel we should applaud.

There’s a tiny silence. She seems to be waiting. Maybe she thinks we should applaud too.

Before anything more can be said, another girl comes in and, while Steffi and I stand there, grabs the second-best bed, and within ten seconds, four more girls race in, and the next thing we know we’re stuck with the only two beds left in the bunk. One is next to the toilet, and the other is under the hole in the wall.

We both shrug and move to the closest bed. There’s no real choice, since they’re both such beauties. I end up under the hole. I hope nothing big crawls in while I’m sleeping.

There’s a lot of introductions around, and with the exception of Dena Joyce and maybe Claire everyone else seems pretty okay.

There’s a Liza from New Jersey who Steffi knows from last year. They were in the same bunk. And the Mackinow twins—I’ll never learn to tell them apart. Alexandra from Boston, who looks very nice, and Claire, who’s got a black mark against her from the beginning. She’s a friend of Dena Joyce, a Miss Perfect type. I can tell already we’re not going to hit it off

.

Before anyone can unpack, the PA starts screaming a frantic announcement. “Attention all camper-waitresses. Attention all camper-waitresses.”

“My God!” I say. “What’s wrong?”

“It’s nothing, take it easy,” Steffi says. “It’s only Edna at the office. She always makes everything sound like a five-alarm fire.”

“You should hear her when she’s really excited,” Liza says, and then she starts laughing about some time last year, but it’s cut off by the rest of Edna’s announcement.

“All camper-waitresses report to the flagpole. Immediately. Right this minute! On the double! Let’s go, girls! Ten … nine … eight … seven … Move it, girls! … six …”

“Hurry, everybody!” Steffi shouts, flinging her bags on the bed, grabbing my hand and yanking me out the door. “It’s the gargoyles.”

“Oh, no,” Liza moans, flying after us. Now everybody, even the cool Dena Joyce, is beating it down to the flagpole, wherever that is. Steffi’s got my hand, and I never saw her move so fast.

From all directions, the sixteen camper-waitresses come running. All the while the shrill command of Edna can be heard over the pounding, panting girls. I’m dying to ask Steffi what’s going on, but I’m running too hard to get out the words. There’s such a mob behind us that we’re almost rammed into the flagpole.

“What’s going on?” I finally find enough breath.

“Later, Torrie, later. For now just stand next to me with your hands at your sides.”

“Is this a joke, Steffi?”

“No, no. Not in the front line,” she says, pulling me into the second tier behind two of the tallest girls in the group.

“I can’t see,” I protest.

“Neither can they.”

Just then all sound stops. It gets so quiet you could hear a pin drop. That’s even quieter than you think, since we’re standing on grass. I can’t see past the girl in front of me, but I see everyone else turn their heads toward the side nearest the administrative offices. I see them following something with their heads until the whole group is looking straight forward.

I peek around between the two giants in front of me. Oh God! I’m sorry I looked. I pull back and turn my shocked face toward Steffi.

“Nothing’s perfect,” she whispers, and snaps he head forward again.

So do I, only now for some reason the girl in front of me has switched places with her partner and I have no trouble seeing what had to be the gargoyles.

Without hesitation, a broad-shouldered, two hundred pound monster lady, a hands-down winner for prison matron of the year, introduces herself.

“Welcome,” she spits out at the quaking group. “I am Madame Katzoff, and this,” pointing to a skinny little man next to her, dressed for riding in jodhpurs and boots and riding crop, “is Dr. Davis.” The only thing Dr. Davis is missing is a monocle—otherwise he’s a perfect old-movie Gestapo officer.

He smiles, and we’re all ready to turn in our mothers.

“Who are these people?” I ask Steffi, but all she does is gulp.

Maybe they’re just passing through.

“You!” Madame Katzoff shouts, and it looks like she’s pointing in my direction. “You!” Again, but this time the shout has a built-in growl. Poor ‘you’ whoever that is. I look around.

But everybody is looking at me.

I look at Steffi, and she shakes her head yes.

My God, I’m you. Some place way back in the bottom of my throat I find enough of a squeak to answer, “Yes, ma’am.”

“If you have any questions, ask me. That’s what we’re here for. Right, Dr. Davis?”

He does another one of those terrifying smiles cracks his crop against the ground, and shakes his head. For some strange reason he doesn’t click his heels.

“Now, your name?”

“Victoria Martin.”

With that, Dr. Davis consults a chart he has, and stretching up on his toes, he whispers something to Madame Katzoff.

“Thirteen.”

“Huh?”

“You,” she snaps, “you’re thirteen.”

“No, ma’am, I’m sixteen.”

“I know that, but your number here is thirteen. We don’t use names. Now, thirteen. What is the question that was so important as to hold us up for a full …”

Dr. Davis supplies the time. “Four minutes.”

In all my entire head there is not one question. So I just shake the whole stupid thing and say, “I’m sorry, ma’am, but I forgot.”

“That will cost you a fifty-cent fine,” she says, and goes right on.

Fifty cents! What is that all about?

“Let me read you a few of the rules and regulations that are going to make summer at Mohaph a joy for everyone,” she continues. “Dr. Davis and I think the best way to start any day is singing. Don’t you agree, girls?”

“Yes, absolutely,” lots of heads nodding in agreement. It sounds okay to me. Maybe I misjudged them.

“Good,” Madame Katzoff says, flashing a carnivorous smile. “Then be here lined up in front of the flagpole every morning …”

All right.

“… at six thirty. In your uniform, with the caps. Following the flag-raising and the camp song, there will be daily instruction and appointment of volunteers.”

“Appointment of volunteers?” I whisper to Steffi, but I’ve lost her. She won’t even look at me. Before I can poke her, Madame Katzoff launches into a list of our duties.

“Each waitress will have two tables …”

Not so bad.

“… of twelve kids and three counselors.”

That’s thirty humans!

“She will be responsible for seeing the tables are wiped clean and set, the trays are washed, the glasses sparkling, and the Batricide room is spic and span….”

“Steffi, what’s the Batricide room?”

“The kitchen after we disinfect it.”

“There will be fifty-cent fines for the following infractions of the rules,” the matron, I mean, Madame Katzoff, continues, and for the first time both she and Dr. Davis smile. “Lateness, talking back, peanut butter and jelly on the tables or chairs, spilling, dripping, unpressed uniforms, missed curfews, smoking, drinking, sloppy bunks, oversleeping, undersleeping, bikinis on the soccer field …” and on and on she goes. I panic.

“I’ll never remember all that,” I whisper to Steffi.

Without moving her lips she says something that either sounds like, “Everything’s going to be all right,” or “We’ll never make it through the night.”

In pure Steffi style I ask myself, “Could this be a horrendous mistake or what?”

Two

Okay. It’s not exactly what I expected, but there are some good things about it. For one thing, I have my best friend with me for the whole summer. The rest of the camp is beautiful, I love the country air, Madame Katzoff isn’t my mother, Dr. Davis isn’t my doctor, and nothing larger than a mouse or a bat could possibly get through the hole in the wall over my bed. And I don’t have to worry about them because, as I’ve been assured a thousand times, they’re more afraid of me than I am of them.

These are some thoughts jumping around in my head while I try to unpack my things. It’s not an easy job, because there is no possible way to jam everything into the tiny cubbies alongside our beds. Everyone has the same problem, so we all arrange to leave most of our clothes in suitcases at the foot of our beds, which leaves about an inch and a half of floor space in the bunk. There’s sure to be a lot of knocked knees and stubbed toes this summer.

In a way it’s kind of cozy fitting everything into this little space. Luckily I brought up a couple of new posters and remembered to throw in some thumb tacks. First thing I do is hang one of them over the hole above my bed. It may not be strong enough to stop the rodent invasions but at least I’ll hear them, which will give me time to move my head so they don’t drop down on my nose.

“You’re not going to leave

that vomitous thing up on the wall, are you?” That, of course, is Dena Joyce talking about my Stones poster.

“Not if everybody hates it. I thought it was pretty hot. What do you think, Steffi?”

“I like it. Liza?”

“Really hot. I have the same one at home.”

Dena Joyce turns to her honcho, Claire. “Do you like it?”

“Yuck … it’s the pits.”

One for Dena Joyce.

Now she turns to the Mackinow twins. They shrug their shoulders sort of agreeing with her. They’re funny, the twins—okay, but kind of like sheep who follow whoever gets to them first. Most twins like to be different, but not the Mackinows. They seem to do everything the same, even dress alike. Now Alexandra has the deciding vote. I’m not taking any chances. I get to her first.

“What do you think, Al?”

“It’s okay with me.”

That makes it even. I really do want to be nice since we have to live together all summer, so I suggest we toss for it. Dena Joyce says heads and wins.

Later Steffi tells me that Dena Joyce always wins. She’s that kind of person. She’s awful, but she always gets her way. You know how you see that happen in movies? The bad person always seems to get her way.

I take the poster down, and now I have that huge hole again.

“That’s better,” Dena Joyce says, rubbing it in.

I’m stacking that up in the back of my mind for sometime in the future when I can pay her back. And I will, too.

That day, after dark, Steffi and I are alone on the porch. She’s sitting on the railing, risking her life, and I’m balanced on the only step that’s still in one piece.

“Are you sorry you came or what?” she wants to know.

“Absolutely not,” I tell her, and I mean it. “It’s going to be great once we get things under control.”

“You’re the best, Torrie. You really are. I guess I just didn’t remember how, well, not perfect it was. All I remember is Robbie, and he is perfect.”

Runaway

Runaway The Sweet Life #2: Lies and Omissions

The Sweet Life #2: Lies and Omissions Little Crew of Butchers

Little Crew of Butchers Before Gaia

Before Gaia Save Johanna!

Save Johanna! Kill Game

Kill Game Sex

Sex Bittersweet

Bittersweet Wired

Wired Twins

Twins When Love Dies

When Love Dies Too Good to Be True

Too Good to Be True Chase

Chase Cutting the Ties

Cutting the Ties Amy's True Love (Sweet Valley High Book 75)

Amy's True Love (Sweet Valley High Book 75) The Perfect Girl (Sweet Valley High Book 74)

The Perfect Girl (Sweet Valley High Book 74) Kiss

Kiss Sweet Valley Confidential: Ten Years Later

Sweet Valley Confidential: Ten Years Later Dear Sister

Dear Sister Second Chance (Sweet Valley High Book 53)

Second Chance (Sweet Valley High Book 53) Killer

Killer Secrets and Seductions

Secrets and Seductions Dangerous Love

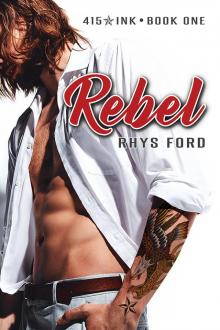

Dangerous Love Rebel

Rebel Shock

Shock Fearless: No. 2 - Sam (Fearless)

Fearless: No. 2 - Sam (Fearless) Racing Hearts

Racing Hearts White Lies (Sweet Valley High Book 52)

White Lies (Sweet Valley High Book 52) Fake

Fake Liar

Liar Flee

Flee Two-Boy Weekend (Sweet Valley High Book 54)

Two-Boy Weekend (Sweet Valley High Book 54) Love & Betrayal & Hold the Mayo

Love & Betrayal & Hold the Mayo Blood

Blood Double Love

Double Love Normal

Normal Betrayed

Betrayed My First Love and Other Disasters

My First Love and Other Disasters Wrong Kind of Girl

Wrong Kind of Girl Naked

Naked The Sweet Life

The Sweet Life The New Elizabeth (Sweet Valley High Book 63)

The New Elizabeth (Sweet Valley High Book 63) Blind

Blind Lost At Sea (Sweet Valley High Book 56)

Lost At Sea (Sweet Valley High Book 56) My Mother Was Never A Kid (Victoria Martin Trilogy)

My Mother Was Never A Kid (Victoria Martin Trilogy) Agent Out

Agent Out Tears

Tears Perfect Shot (Sweet Valley High Book 55)

Perfect Shot (Sweet Valley High Book 55) Regina's Legacy (Sweet Valley High Book 73)

Regina's Legacy (Sweet Valley High Book 73) Escape

Escape Freak

Freak Sam

Sam